Religious hatred has no place in Celtic’s history. In recent months there has been a lot of division within the support about the place of Irish politics at Celtic Park. One of the main reasons for this debate is the “soon there’ll be no Protestants at all” add-on that has resurfaced at away matches. However, there’s no debate to be had.

We can all agree that that disgusting sectarian add-on has no place in Paradise, but it also has absolutely nothing to do with Irish Republican- ism. To conflate the two, or to compare Irish Rebel songs with that bigoted slur is the height of ignorance. Quite simply, religious hatred has no place in Celtic’s history, but Irish politics does… along with charity, faith, and football.

The freedom of Ireland was never far away from the minds of those involved in Celtic’s beginnings. The likes of William McKillop (Irish Nationalist MP for North Sligo and South Armagh) and Patrick Welsh (Irish Republican Brotherhood volunteer on the run who was key to Willie Maley signing) were among the club’s founding fathers, while Michael Davitt (Irish Republican Brotherhood member convicted of gun running) was named as the club’s second Patron and was invited, by Brother Walfrid et al, to lay the centre sod of shamrock smothered turf at the new Celtic Park in 1892.

https://celticfanzine.com/product/annual-magazine-subscription/

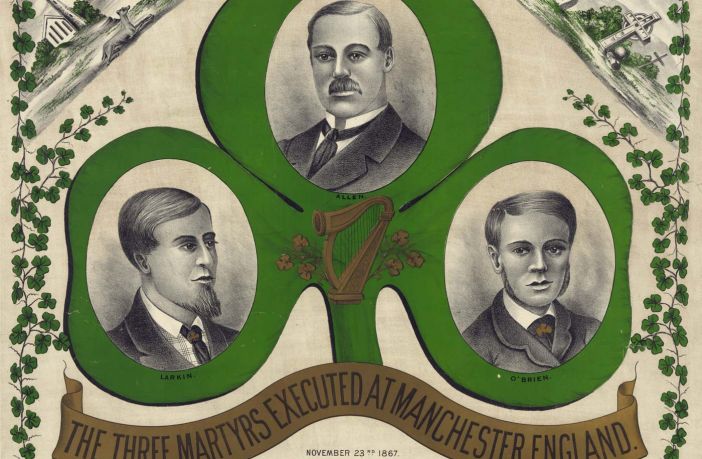

During said turf laying ceremony, God Save Ireland, a song about three then recently hanged Fenians known as the Manchester Martyrs, was performed by its composer T.D Sullivan. This was nothing unusual as songs of an Irish Nationalist nature were regularly sung by the club’s early committee members at functions, and Celtic were the only sporting organisation to send an official delegation to the 1896 Irish Race Convention in Dublin, which was designed to plot a route towards Irish Home Rule.

Those same Nationalist songs – A Nation Once Again, Wearing of the Green, and The Dear Little Shamrock – were sung by our earliest supporters on the terraces and aboard Brake Club carriages before being passed down the generations.

Ballad and song provided the link to home for the first exiled Irish men and women, and naturally that musical heritage was handed to their successors who have never stopped enjoying them among the Celtic faithful. It is not only a celebration of those who founded the club, or the community for which they primarily did so, but a celebration of many within the support’s own familial history.

Irish Rebel songs continue to be a major part of the matchday experience in the stands, on supporters’ buses and in pubs. The fans’ sense of Irish identity, and the political manifestation of its expression, has strong historical relevance.

Indeed, the Irish diaspora always kept a keen eye on the ancestral home and were inspired by the main cause moving from Nationalism to Republicanism, and the quest for Home Rule being replaced by outright independ- ence after the Easter Rising. The Scots Irish were enraged by the undemocratic partition of Ireland, just a few short years after the majority of the country had demonstrated its desire for an independent 32 County Repub- lic in the 1918 General Election. Witnessing six counties being torn from the other 26, Irish national sovereignty and democracy being violated, incensed those among the diaspora.

Meanwhile, the subsequent pogroms, intern- ment, and the Special Powers Act being inflicted upon Northern Nationalists did little to quell the Irish community’s boiling indignation as the new ‘Northern Ireland’ statelet violently rumbled through its infancy.

https://celticfanzine.com/product-category/t-shirts/

It must be remembered that long after An Gorta Mór, there was another wave of Irish immigration to Glasgow in the 1920s (time of partition). These immigrants particularly came from border counties such as Donegal, Sligo & Cavan. Anti-partition feelings were very strong in those regions of Eire and Eamon De Valera, President of the Irish Free State from 1919 to 1922, once remarked:

“The financial contribu- tion to the Irish struggle from among the Scot- tish communities was in excess of funds from any other country, including Ireland.”

Much like the descendants of the first Irish immigrants to arrive in Scotland, the politics, songs, and culture of Ireland continued to be inherited by the offspring of those 1920s expatriates (Irish migration to Scotland has also continued a smaller scale since).

After the Civil War ended across the water, almost 50 years of discrimination against Northern Catholics in housing, voting and employment rarely went unnoticed. The emergence of the Civil Rights movement, followed by the Battle of the Bogside, the burning of Bombay Street and the long struggle for a United Ireland, radicalised the Irish around the world to varying degrees. Throughout these times the presence of Ulster based fans at Parkhead, and the Glasgow Irish experience of discrimi- nation mirroring the oppressive hardships endured (to a lesser extent) by those in the North of Ireland, made songs about these events feel relevant to the Celtic faithful.

Speaking of fans based outside of Scotland, it is important to note how they also impacted upon the faithful’s political identity. Celtic enjoys huge support from the global Irish diaspora and across Ireland itself. These people solidify ties to the country and often hold Nationalist or Republican views.

However, the most influential cohort from a historical perspective has been those who previously followed Belfast Celtic until the Irish club’s demise in 1949. It was then that Paradise was lost in Antrim and found in Glasgow. As a result, Celtic inherited the sole allegiance of a fervent support, who would soon become politicised by the unfolding of the Troubles.

Celtic was to become their social outlet, and a place to freely express themselves, as the Flags & Emblems Act had criminalised public expression of Irish identity in the occupied six counties. The presence of so many Belfast Celtic fans, and subsequently their descend- ants, at Paradise added to the eminence of Irish culture and further radicalised an already politically minded diaspora.

Political songs were once the mainstay of the Celtic songbook, but although they continue to play a key role in the match day experience, they have become the preserve of the away support and vocal pockets at home games since the mid-1990s.

Those who sing them contend that Irish Rebel songs tell the story of the struggle for Irish freedom, commemorate patriots, and remember the hardships endured by the Irish over the years. Famous musician Derek Warfield, in his Celtic & Ireland in Song and Story book, describes them in the following way

“These historical songs and ballads have been used by the Irish people to defend and propagate the many related causes of Ireland. They have been known to educate and inform, to bring knowledge and truth through literature and poetry. Above all, the lyrics and tunes in Celtic & Ireland in Song and Story (which are sung by the Celtic support) are far reaching, educational, and of course, provide a great source of pleasure.”

https://celticfanzine.com/product-category/celtic-collectors-badges/

For a considerable section of the Celtic support, Irish Repub- lican ballads are the foundation of their cultural identity, in combination with non-political songs. Politics is one of the distinct things about Celtic and is the reason why the club’s Irish based support is more concen- trated in the North of Ireland. In that sense, away games are probably more reflective of a subgenre within Irish culture, with the home matches largely reflecting the type of folk songs that the wider Irish population may enjoy – the likes of the Fields of Athenry, Let the People Sing, Lonesome Boat- man etc.

This subgenre outrages some unsympathetic people in the 26 counties of Ireland that already have their freedom and has coveted a lot of controversy in Britain. Although these songs do not contain sectarian litera- ture in their lyrics, they are believed to be sectarian by many ill-informed people in Britain.

More accurately, they remember and laud those who are viewed as terrorists by Free Staters and the British public, most of whom have little understanding of the Troubles. To explain why sections of Celtic fans (and the Irish diaspora around the globe disagree with such opinions, even if they share a disdain for some of the actions undertaken by the organisations they sing about, it would require an analysis of Irish history, delving into the policy of Ulsterisation and suchlike, which is impossi- ble to provide in full comprehensivity here.

Political websites or books would be more appropriate platforms for such complex content to be digested, and to get a greater insight into the accurate nature of the recent conflict in Ireland but suffice it to say that the anti-imperialist struggle to achieve national liberation from a foreign invader and the true cause of the war (a civil rights struggle beaten into the ground) do not match the ‘medieval religious squabble’ or ‘terrorist’ narratives presented by the media.

If a small section of our fanbase is too ignorant to read about the subject, see through British and Irish Government propa- ganda, or recognise Rebel songs as a legitimate form of cultural expression for the majority of our supporters, who hail from Irish extraction, then that is their problem.

They can carry on believing that ten men gave their lives on hunger strike because they hated Protestants if they like. Just as they can denounce the IRA for their bombing campaigns in pursuit of freedom (despite a very low percentage of civilian casualties), while likely seeing nothing wrong with the RAF bombing Berlin during the Battle of Britain or killing hundreds of thousands of civilians to retain freedom during WWII. Such ignorance is reminiscent of the lack of education displayed by the bigots who desecrated a song about Irish unity with a derogatory add-on aimed at Protestants – totally unaware that modern Irish Republicanism is a secular move- ment which was founded by Presbyterians such as Wolfe Tone, Henry Joy McCracken, Samuel Neilson etc.

https://celticfanzine.com/shop/

Whether one likes rebel songs or endorses previous armed struggles is a personal matter, but what nobody can deny is the fact that the politics of Irish freedom have a clear place in Celtic’s history and the heritage of the communities from which its core support is derived.

Religious hatred has no place in Celtic’s history. On that note I will bring my rant to a close.

https://baraqudamercurepattaya.hotels-boutique.com/product/celtic-festival-2023/

Copyright 2018 Celtic Fanzine | Developed by Blueberry Design